By Libuseng Nyaka

QWAQWA-‘Lela le lapileng ha le na tsebe (A hungry person acts without considering the consequences of their actions).’

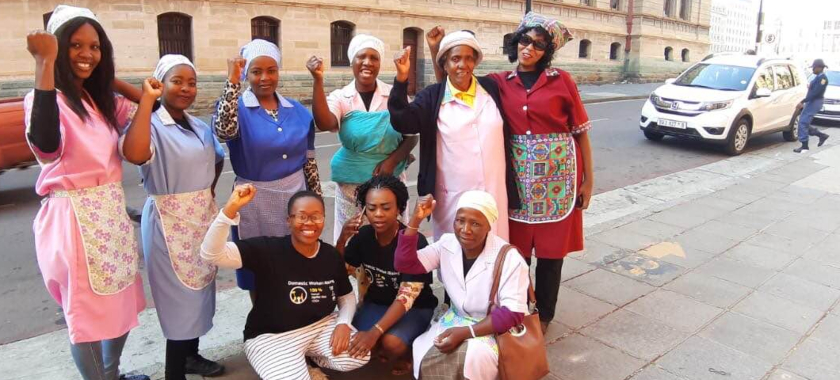

This old Sesotho idiom could not be more true for jobless women of Makhalaneng in the Eastern Free State, who ignore lockdown regulations as they go from house to house in search of domestic work.

One of them, Dimakatso Mokoena (35) had this to say about her predicament: “It is heart-breaking to helplessly watch your child suffer from hunger. Before lockdown we used to earn money by washing people’s clothes and cleaning their houses.

“What makes it even worse is that we do not qualify for the government relief fund as we were just casual workers who were not even registered for the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF). We tried to comply with the restrictions after receiving our child support grant but now we are not coping anymore; we are forced by circumstances to risk our lives by exposing ourselves to contracting this Covid-19.”

Mokoena is worried that even if they survive the highly contagious and deadly Covid-19 which infected about 20,000 people and claimed over 300 lives in South Africa, she and her kid would still die of hunger if does not take action.

“I am stuck between a rock and a hard place. But I choose to go out there and look for a job so I can put something on the table”

Another domestic job seeker, Mponeng Mbatha (38) is equally distraught.

“I am stuck between a rock and a hard place. But I choose to go out there and look for a job so I can put something on the table,” Mbatha said.

She said the lockdown has hit her real hard, but leaving her child to die of hunger while she watches is not an option.

“Before the lockdown I used to work as a street vender selling vegetables and fruits where I would at least raise R200 a day to supplement the child grant of R350 per month. But life has become unbearable with her son always at home and supplies drying up in less than a month.

“We used to save on food with the school feeding scheme; our children would eat only one meal at home.”

Mampho Mofokeng is even worse off. At 58 years of age, she is too young to qualify for the senior citizens’ social grant, and too old to get any job. Not having a qualification does not help her situation.

“We do odd jobs; I cannot operate from my house. I have to go out and hustle,” she said.

The government, through the social development department, has set up an emergency relief fund for people like Mofokeng, who are tipped to receive a monthly grant of R350. One glitch though: potential beneficiaries have no idea how to access it.

“We have queued up at the local social development offices but we could not be assisted as there were too many people. We are unable to arrive early because we live far from town and taxis start work at around 5:00am when queues have already swelled.”

More Stories

Advertorial | Maluti TVET Graduation Ceremony

Manapo children receive gifts

MEC Mbalula joins farmers, cops to fight livestock theft